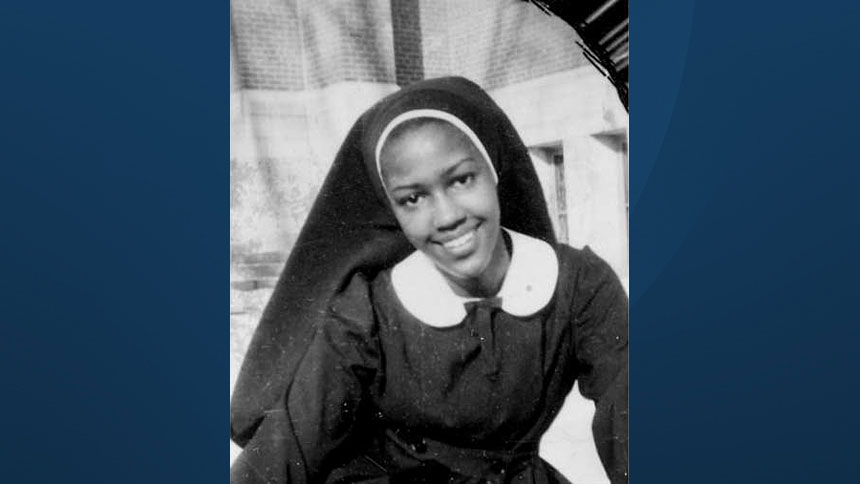

Sister Thea Bowman was the granddaughter of a slave, an advocate for racial justice, and the first African American woman to address the U.S. bishops' conference. Two years ago, her sainthood cause was opened.

“She was an outstanding teacher, and she was an outstanding speaker. And she had a voice like an opera star, and she could sing really beautifully, and people loved to be with her,” said Sister Charlene Smith, a member of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration (FSPA).

“I often say she was a whole lot like Jesus. People love to be around her, and I was one of those people that was lucky enough to be around her.”

Smith, who was friends with Bowman for 35 years, recounted the impact that Bowman made on many of those around her. In 2012, Smith co-authored a biography of her friend, entitled, “Thea's Song: The Life of Thea Bowman.”

At age 51, Bowman became the first African American woman to address the U.S. bishops' conference. Wheelchair-bound and fighting cancer, she delivered a memorable address about race and Catholicism before inviting the bishops to join her in singing and swaying to a Negro Spiritual.

That spunk, Smith told CNA, was part of Bowman’s charismatic personality as she traveled and taught and spoke around the country.

Sister Thea was born Bertha Bowman in Yazoo City, Mississippi, in 1937 to a lawyer and a teacher.

Although she was raised Protestant, she decided to become a Catholic at the age of nine. Visiting a variety of Christian denominations, she was moved by the kindness and generosity of the Franciscans Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, whose school she subsequently attended.

When she turned 15, she moved to Wisconsin and entered the order's novitiate. Although her parents tried to persuade their daughter to enter an African-American community, she was determined to enter the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, whose warmth and love had drawn her to the Catholic faith six years prior.

At the time, she was the first and only Black sister of the community in La Crosse. Smith said Bowman encountered some instances of racism even within the convent.

“I never saw any example of racism extended to Sister Thea when she was in our community, but there are sisters from other communities, African American sisters, to whom Thea apparently mentioned that once in a while, some of our older sisters, who had never been around anybody who was African American, were not always positive about Sister Thea,” she said.

When she began teaching at a Catholic elementary school in La Crosse, Bowman would teach about racial diversity and about the importance of love.

“She taught children to use their hand. And the five fingers were the five different colors of skin, black and brown and yellow and red and white,” Smith said.

“And she knew that we were all not a melting pot. She was never very interested in that particular metaphor. She was a whole lot more interested in saying that we are more like a salad,” Smith continued. “So when you are a salad, you don't lose your characteristics, you remain individuals. And the whole point is to love one another. And that's what she did.”

As the civil rights movement grew in the years that followed, Bowman worked to advance racial justice. She helped establish the National Black Sisters Conference and advocated for an increased representation of African American people in Church leadership. She called for more encounters between white and non-white Catholics and for a welcoming of music from different cultural backgrounds.

Bowman became a noted public speaker and traveled around the country, talking about race and the Catholic faith. She continued to travel and teach even after being diagnosed with breast cancer in 1984, even landing an interview with 60 Minutes.

In 1989, Bowman delivered what would become a famous speech at the spring meeting of the U.S. bishops’ conference.

“What does it mean to be Black and Catholic?” asked Sr. Thea. “It means that I bring myself, my Black self.

“I bring my whole history, my traditions, my experience, my culture, my African American song and dance and gesture and movement and teaching and preaching and healing and responsibility as gift to the Church.”

Bowman had a profound impact on the bishops, and on many other people who heard her words.

“When that speech was over, they wheeled her off the podium and out into a hall. And one by one, the bishops came to her and knelt before her, in her wheelchair, and asked for her blessing. That's how much they thought about her,” Smith said.

Bowman died March 30, 1990. Her canonization cause was opened by the Diocese of Jackson in 2018.

Smith said Bowman’s impact lives on after her death, with schools named after the sister, events held in her memory, memorials established in her honor, and at least 40 books mentioning her story and influence.

Smith said Bowman would likely find hope in the recent protests demanding racial equality and justice in the wake of George Floyd’s death.

“Right now this is a time when we're learning. I think the people in the United States are learning a whole lot more about our history, how we were terrible to the Native Americans and how we were terrible to the African Americans, and so we're learning history,” she said. “Thea knew all of that and she let it be known that she knew that.”

“I’m sure she's watching what's going on in the United States. And I think she's cheering for the African Americans and all of the people who have been subjected to pain and injustice,” Smith continued. “She was very much concerned that people be treated fairly, be treated as children of God. So she'd be happy with what's going on.”